Meeting low-wage workers where they live -- literally

When employers think about the well-being of their low-wage workers, they tend to focus on a few areas of concern where they might be able to make an impact: health care affordability, encouraging better health behaviors, ensuring timely and appropriate access to care, and promoting use of preventive services. Then they might think about financial well-being programs that help employees with budgeting, paying down student loans, buying a first home and retirement planning.

If that all sounds familiar and you are ready to dig a little deeper, try spending some time looking at the characteristics of your low wage workforce. For several years, we’ve been developing “employee personas” for clients to provide a better understanding of the everyday lives of employees. Where do they live and what kind of housing do they live in? How big is their family -- and is it multi-generational? How do they get to work? Is their transportation reliable? Are they concerned for their safety at home, commuting, or at work? Where do they shop and how do they spend their money? What do they do in their free time? What is important to them?

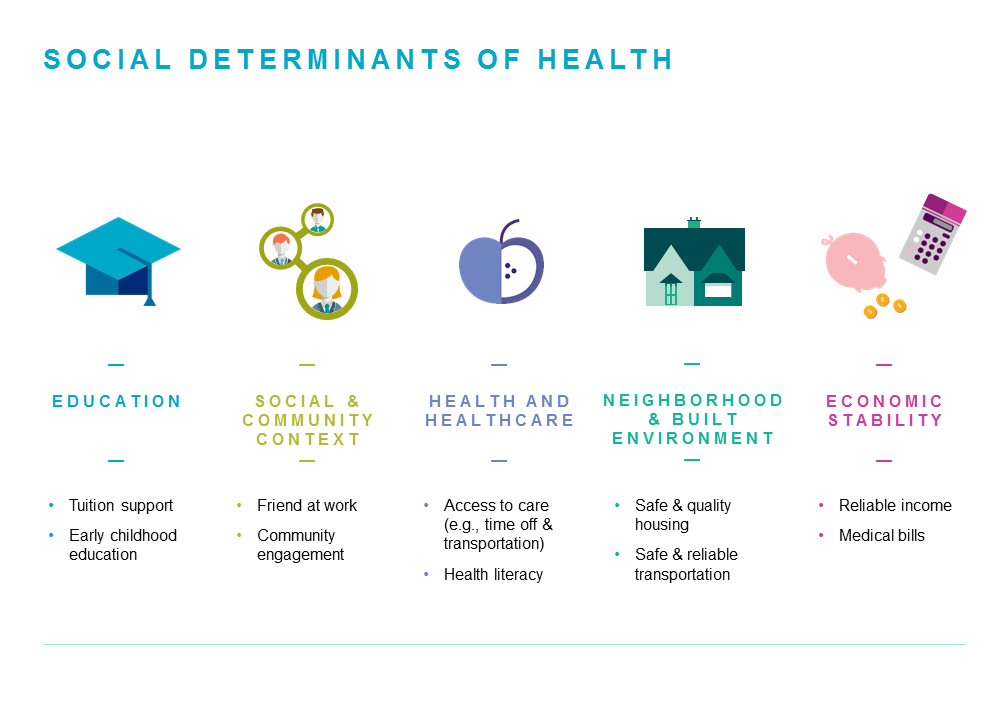

Using the personas, we have come to understand that for most low-wage workers, the first order of business is to focus on basic needs. These span the physiological needs at the base of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (e.g., food, water, sleep) and secondary needs, focused on safety. These needs must be met before one can be fully present at work and able to focus on personal health. The social determinants of health, shown in the diagram below, are the factors that influence how easy or difficult it is for someone to have their basic needs met. These factors have been shown to have a bigger impact on someone’s own health status and productivity than their DNA and how much they sleep.

How can you work with social determinants of health to improve the quality of life for your employees, and maybe even improve retention at the same time? Let’s take just one example. Say you learn that many employees take a train to work that runs well – when it’s running. Unfortunately, it’s not the most reliable, and workers on the early morning shift who arrive late too often run the risk of losing pay, being disciplined, lectured or fired. Employers can help relieve this source of stress offering a van service to get people to work for an early shift, or adjust work shifts to make it easier for their people to arrive on time.

Because every employer’s situation is different, there’s no one way to work with the social determinants of health model. But this lens provides new focus for employers to better engage with workers where they need it the most. And in a tight labor market where turnover is costly, this approach might just be the differentiator you are looking for.

Related products for purchase

Related Solutions

Related Insights

-

US health newsNew survey data reveals the strategies employers are considering to slow health benefit cost growth in 2026.

-

US health news

SCOTUS on gender-affirming care for minors: Employer takeaways

The US Supreme Court held that a Tennessee law banning certain medical treatments for gender-affirming care for minors does not violate the Equal Protection Clause… -

US health news

Preventive vaccines and workforce health

Dr. Prachi Nagda discusses the role vaccines play in workforce health to help employers prepare for changes that are coming and decisions that may be needed.