Multiemployer plans get guidance on special financial assistance

A new interim final rule (IFR) from the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. (PBGC) provides guidance on the special financial assistance (SFA) for multiemployer pension plans (MEPPs) under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 (Pub. L. No. 117-2). A companion IRS notice (2021-38) clarifies several issues, including how sponsors receiving SFA should reflect the funds when determining minimum required contributions. Although the IFR is effective immediately, PBGC will consider comments received by Aug. 11 when drafting the final rule. This GRIST provides a high-level review of the IFR’s details and addresses how receiving SFA might affect withdrawal liability, employer contribution rates, collective bargaining and funding requirements. The article also summarizes the relevant application procedures for MEPPs considering applying for SFA.

ARPA’s SFA for multiemployer plans

ARPA created a temporary special fund within PBGC to provide SFA to eligible, poorly funded MEPPs. More than 3 million participants are covered by MEPPs heading for insolvency, and PBGC expects roughly 200 of those plans to be eligible for SFA. PBGC estimates it will pay more than $90 billion in SFA to these plans (but neither ARPA nor the IFR provides a limit on SFA payments). The money needed to make the SFA payments will be provided from the Treasury’s general revenues. PBGC will not have to repay the Treasury, and MEPPs that receive SFA will not have to repay any amount to PBGC.

ARPA’s intent is to preserve these plans’ solvency for 30 years — until 2051. Accordingly, the SFA payout is determined as the excess of a MEPP’s projected obligations for benefit payments and expenses over its projected resources (including current assets, future contributions, withdrawal liability payments and investment earnings) for the period beginning shortly before the SFA application is filed to the end of 2051.

These new PBGC rules will have no impact on employers that do not contribute to MEPPs, nor will they affect employers that contribute to MEPPs ineligible for SFA.

Impact of receiving SFA

A MEPP’s joint board of trustees will make the decision on whether to apply for SFA. That decision is likely to be subject to ERISA’s fiduciary standards and may not be straightforward for some MEPPs. Although SFA will theoretically help a plan avoid insolvency, the way the assistance is structured — as the exact amount necessary to pay for all benefits and expenses through 2051, taking into account all investment returns and contributions between now and then — means that plans can expect to end 2051 with no remaining assets. In effect, the SFA formula applies all contributions made before 2052 to benefits that will be paid over that period, even though the life expectancy of many participants for whom those contributions were made will extend beyond 2052. Plans whose experience is worse than anticipated in the SFA calculation will become insolvent before the end of 2051 without further intervention (i.e., additional government assistance).

Although a plan receiving SFA theoretically could increase contribution rates beyond current levels and thereby remain solvent beyond 2051, most of the plans receiving SFA will likely find that the economics don’t make sense. This is because the projected cost of benefits payable after 2051 will often be quite large relative to the remaining contribution base of affected plans. The remainder of this article therefore assumes insolvency by 2051.

Plans in dire financial straits might be willing to accept almost-certain insolvency in 30 years, given that the alternative may be insolvency much sooner. But accepting SFA has other consequences that may have an earlier impact.

Withdrawal liability

When an employer ceases to participate in (or in some circumstances, reduces its level of participation in) an underfunded MEPP, ERISA imposes a “withdrawal liability” charge. The withdrawing employer must pay an amount equal to a proportionate share of the plan’s unfunded vested benefits (UVBs, the excess of the MEPP’s vested benefit liability over its assets). Withdrawal liability assessments are sometimes onerously large, and employers will often devote significant time and energy to minimize those charges.

Calculating UVBs. Because withdrawal liability calculations depend on a MEPP’s UVBs, including SFA payments in plan assets would reduce withdrawal liability assessments. However, PBGC considers this an indirect diversion of SFA assets to withdrawing employers, making it easier for them to withdraw. That result would go against the statutory mandate to use all SFA assets solely for the payment of benefits and expenses.

Some plan sponsors and benefit professionals had expected PBGC to avoid this outcome by requiring withdrawal liability calculations to ignore SFA payments. Instead, the IFR takes a different approach:

- SFA amounts are included in the assets used to determine an employer’s withdrawal liability, thus reducing UVBs.

- The present value of vested benefits must be determined using interest rates applicable to mass withdrawals of all or substantially all contributing employers. Those interest rates are typically lower (potentially significantly lower) than the rates used by to calculate withdrawal liability for a regular, nonmass withdrawal, leading to higher (potentially significantly higher) UVBs.

These two offsetting factors may lead to lower or higher UVBs and correspondingly lower or higher withdrawal liability assessments, depending on a MEPP’s circumstances, particularly the interest rate ordinarily used for these calculations. (The amount of withdrawal liability actually paid is limited by a separate annual payment calculation, discussed below. As a result, the change in the UVB determination may have little effect on the actual liability of most withdrawing employers.)

The requirement to use mass withdrawal assumptions expires after the later of 10 years or the depletion of the MEPP’s SFA assets. From the plan’s perspective, using mass withdrawal assumptions is generally favorable, since lower rates will produce larger withdrawal liability assessments, making withdrawal less attractive to employers and triggering higher payments from employers that choose to withdraw anyway. (Employers will view this requirement unfavorably for the same reasons.)

Some plans might therefore choose to pay benefits and expenses first from non-SFA assets to stretch their SFA assets out as long as possible, extending the time over which this requirement will apply. However, plans will have to weigh this potential advantage against the lower returns likely to be earned on those assets due to the restrictive investment conditions the IFR imposes on SFA assets. (Plans could theoretically get the best of both worlds by maintaining only a tiny amount of SFA assets, which doesn’t appear to be prohibited by the regulations.)

Some significant MEPPs have adopted rules permitting an employer to make an agreed-upon payment to resolve withdrawal liability exposure and then participate in a separate pool intended to remain fully funded. Whether the receipt of SFA will disrupt these arrangements is not clear.

20-year cap. When an employer withdraws from a MEPP, the plan determines the withdrawal liability assessment and sets a payment schedule, generally requiring quarterly or monthly payments for a period of as long as 20 years. Statutory formulas determine the amount of each payment, so capping the payment period at 20 years frequently means the value of the required payments is less than the total “nominal” liability, especially for severely underfunded plans.

The 20-year cap on withdrawal liability payments doesn’t apply to mass withdrawals. But because an infusion of SFA assets is intended to keep a MEPP solvent until 2051 — at least in theory — plans receiving SFA may be less likely to undergo a mass withdrawal. Thus, the 20-year cap on withdrawal liability payments will often continue to apply.

When a MEPP must use mass withdrawal interest assumptions to determine an employer’s withdrawal liability and this increases nominal liability exposure, the 20-year cap will often insulate the employer from any additional cost.

Settlements. As an alternative to a lengthy payment schedule, an employer may seek to settle its obligation in a single negotiated lump sum. Any such negotiation would take the 20-year cap into account, if applicable. The IFR requires PBGC approval when the initial value of the settled liability exceeds $50 million, even if the proposed settlement amount is less than $50 million. PBGC explains in the IFR’s preamble that this provision will ensure that material settlements are in the best interest of participants and will not expose the agency to unreasonable risk.

Employer contribution rate decreases

Under the IFR, multiemployer plans receiving SFA generally cannot reduce employer contribution rates below the rate specified in the collective bargaining agreement in effect when ARPA was enacted (March 11, 2021), including all increases scheduled to take effect between that date and the expiration of the agreement. This limitation applies for the entire SFA coverage period — that is, from the end of the quarter before the SFA application was filed to year-end 2051. This provision is intended to prevent the indirect diversion of SFA funds to contributing employers by reducing their contributions.

However, the IFR provides an exception when the plan sponsor determines that a rate reduction would lessen the risk of loss to plan participants, as might be the case if the current contribution rates would drive an employer into bankruptcy and lead it to withdraw from the plan. Any rate reduction that would lower annual contributions by more than $10 million and more than 10% of all employer contributions would require PBGC approval.

Collective bargaining

For contributing employers and labor organizations, a MEPP’s receipt of SFA could present difficult issues.

Rehabilitation plans. ARPA provides that multiemployer plans receiving SFA are deemed to remain in critical status (“red zone”) until the end of 2051. Plans in critical status generally must implement rehabilitation plans that specify contribution rates and benefit terms with which contributing employers and unions must comply. A rehabilitation plan is intended to ensure the plan emerges from critical status within 10 years or, if that is not possible, to forestall insolvency for that period. Many MEPPs amend their rehabilitation plan from time to time, some even annually. Neither the statute nor the IFR address how receipt of SFA will affect existing rehabilitation plans or amendments to such plans, though PBGC notes in the IFR’s preamble that MEPPs receiving SFA will remain subject to the terms of their applicable rehabilitation plans.

Withdrawal. A company that maintains an ongoing business and contributes to a MEPP on behalf of its represented employees could conclude a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) that provides for its withdrawal from the MEPP. In some circumstances, the union, not the company, might initiate a proposal for withdrawal.

Each year’s contribution to a MEPP normally is designed to fund a portion of all future benefits payable to current participants. However, the structure of SFA makes it likely that the MEPP will have no assets remaining by the end of 2051. If so, a portion of contributions paid before 2051 for benefits payable after 2051 won’t be available for that purpose. In effect, younger participants will pay for benefits they will never receive: Once the plan becomes insolvent, participants’ benefits will be cut back to the level of the PBGC guarantee, in the absence of additional legislative relief. Unions — especially those with a relatively young covered group — are likely to find this prospect highly unappealing and might propose withdrawal from the MEPP in favor of an alternative retirement arrangement, such as a defined contribution plan.

Withdrawal from a MEPP, even if initiated by the union, will trigger withdrawal liability for the employer. (As noted above, receipt of SFA could raise or lower the net withdrawal liability assessment, depending on each MEPP’s circumstances.) In any event, a CBA that provides for withdrawal from a MEPP and the establishment of an alternative retirement program would require the employer to bear both the cost for a new program plus the withdrawal liability.

Benefit improvements. ERISA generally precludes a MEPP in critical status from increasing benefits unless the increased benefits will be paid for by additional contributions not contemplated in the rehabilitation plan. MEPPs receiving SFA are strictly prohibited from adopting amendments to grant retroactive benefit increases during the SFA coverage period. However, new benefit accruals — which could provide an incentive for more members to participate and thus expand the plan’s contribution base — are allowed.

Proposals for such prospective benefit improvements may be difficult to evaluate, since it’s unclear how to determine whether a given rate increase will be sufficient to pay for an ongoing benefit in a plan anticipated to become insolvent. Contribution rate increases to pay for future benefit improvements could delay insolvency past 2051, but the additional funds would be quickly depleted, since they would be supporting all benefits starting in 2052 — not just the benefit increases for which the higher contributions were intended to pay.

The rules applicable to benefit improvements for MEPPs that receive SFA are complex. If an employer and its union seek to negotiate benefit improvements, both sides might consider doing so outside the MEPP.

Minimum funding requirements

Under ARPA, SFA amounts are disregarded when calculating a MEPP’s minimum required contribution, but the statute didn’t specify how to implement this exclusion. In Notice 2021-38, IRS states that SFA amounts are not reflected in a plan’s assets for any purposes when determining contributions, including in the plan’s funding standard account.

MEPPs that are eligible for SFA either have failed to maintain compliance with minimum funding requirements — and therefore have developed an accumulated funding deficiency (AFD) — or are projected to do so. In theory, the addition of a substantial SFA payment to such a plan would lower its AFD. However, the exclusion of SFA assets from minimum funding calculations means that the AFD will not change. Instead, over time, as SFA assets are used to pay benefits, the plan’s benefit obligations will decline, but the plan’s recognized assets will not. This will create an artificial actuarial gain that will be amortized over time, thus reducing the plan’s minimum required contribution and ultimately reducing the AFD relative to what it would have been without the SFA.

Under the current regulatory structure, MEPPs in critical status, like all MEPPs that will receive SFA, are not subject to any excise tax for incurring an AFD. So any funding anomalies attributable to excluding SFA from plan assets will have no direct impact on the MEPP. However, a change in tax treatment could subject a MEPP to an excise tax on AFD, depending on how IRS interprets certain ambiguous provisions of the Internal Revenue Code.

Some MEPPs have attempted to assess a ratable share of the plan’s AFD against a withdrawn employer in addition to statutory withdrawal liability. The exclusion of SFA assets for minimum funding purposes means that withdrawing employers in these plans will see no near-term reduction in the AFD assessment, since the AFD will not change. Whether such assessments are enforceable remains a subject of litigation. However, the exclusion of SFA assets from funding calculations — especially if coupled with lower withdrawal liability as a result of SFA — could cause other MEPPs to consider introducing such assessments to avoid reducing employers’ withdrawal costs and potentially to extend solvency beyond 2051.

Restoration of benefits

As a condition for receiving SFA, MEPPs that have reduced benefits pursuant to the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014 (MPRA) must reverse those benefit reductions and make retroactive payments to participants. Although the cost of these benefit restorations counts toward the benefit obligations used to determine the amount of SFA, this change nevertheless represents an increase in plan costs. For a MEPP otherwise projected to remain solvent beyond 2051, trustees will have to weigh whether restoring benefits and accepting SFA that is projected to enable the plan to remain solvent only through 2051 is preferable. A MEPP’s decision to apply for SFA may affect an employer’s decision to continue participating in the MEPP.

SFA procedures and timing

In addition to the IFR, PBGC has published a web page with several additional resources — including filing instructions, templates, an application checklist and more — for MEPPs applying for SFA. ARPA does not require SFA-eligible MEPPs to submit such an application. MEPP sponsors may develop their own estimate of the amount of SFA that they might receive and take such estimates, as well as other consequences of receiving SFA, into account in deciding whether to apply.

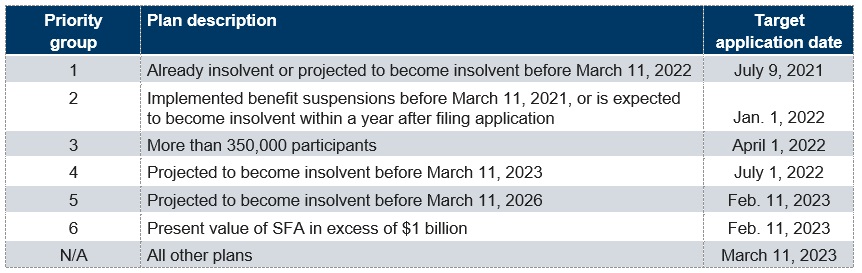

PBGC will process applications under a schedule based primarily on the MEPP’s solvency status, with plans in six identified priority categories taking precedence over all other plans. The most seriously impaired plans can file applications immediately (starting in early July), while plans in the last priority category can’t apply until Feb. 11, 2023. Plans not in a priority category cannot submit applications until March 11, 2023. Applications must be filed no later than Dec. 31, 2025, but a plan can revise and refile its application an unlimited number of times before Dec. 31, 2026.

The table below shows the full application schedule:

ARPA requires PBGC to process applications within 120 days, but the agency is concerned about its capacity to handle a flood of applications, even with the staggered application schedule. PBGC will therefore accept only as many applications as it expects to be able to process within 120 days. After that, the application period will temporarily close until PBGC can process more applications.

Once PBGC has approved an application, it will pay the SFA in a single lump sum within 60 days. All funds will be paid out by Sept. 30, 2030.

Request for comments

PBGC invites comments on the IFR from any interested parties and specifically requests comments on these topics:

- Circumstances warranting an exception to restrictions on reductions in employer contribution rates, transfers or mergers, and settlement of withdrawal liability

- The requirement to invest SFA funds in investment-grade fixed-income funds

- The requirement to maintain one year’s worth of benefit payments and expenses in investment-grade fixed income

Comments on the IFR must be submitted by Aug. 11, 2021.

PBGC also notes in the IFR that it intends to propose a regulation of general applicability that will address the actuarial assumptions to use in withdrawal liability determinations. It has not yet invited comments on this issue.

Related resources

Non-Mercer resources

- American Rescue Plan Act FAQs (PBGC, July 29, 2021)

- Interim final regulation, Special financial assistance by PBGC (Federal Register, July 12, 2021)

- Notice 2021-38 (IRS, July 9, 2021)

- Pub. L. No. 117-2, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (Congress, March 11, 2021)